- Daily Life at Pemi

- Education at Pemi

- Nature

- Newsletters 2016

- Summer 2016

A Look at Pemi’s Day-to-Day Nature Program

2016 Newsletter # 5

by Larry Davis, Director of Pemi’s Nature Program

In years past, I have used the opportunity to write a newsletter as a chance to wax philosophic about the importance of getting children out into nature, about the excitement of some of our special activities (such as caving), or about the history of natural history at Pemi. It has been a while since I described our day-to-day program. So, for the rest of this newsletter, that’s just what I’ll do.

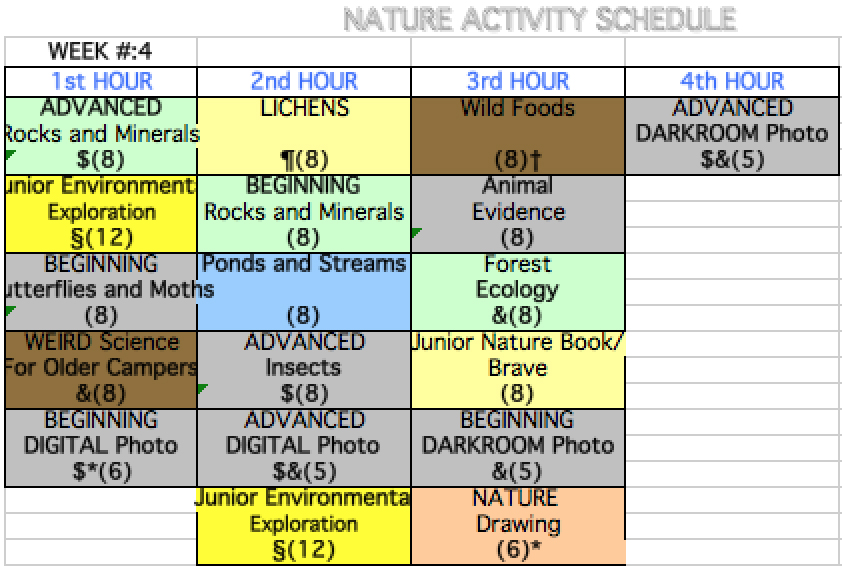

Each week we offer 14-17 different nature occupations. Some of these are available every week and others may appear only once. You’ll find a glimpse of this week’s offerings at the end of the newsletter. All told, 35-40 nature occupations are available over the course of a summer.

Our scope is broad and includes both natural history topics—such as ponds and streams, forest ecology, rocks and minerals, and butterflies and moths—along with related fields such as nature photography and drawing, orienteering, bush lore and “weird science.” Much of what we teach is available at both beginning and advanced levels so that a Pemi camper can continue to explore new aspects of the natural world as he progresses through his career at camp. What follows is a description of just a few of our offerings.

Beginning Occupations

Our beginning activities follow a set lesson plan and are typically offered every week during the summer. They are designed to serve as an introduction to one or more aspects of nature. Topics include, Butterflies and Moths, Non-Lepidopteris Insects (that’s everything except butterflies and moths), Rocks and Minerals, Ponds and Streams, Digital and Darkroom Photography, among others.

Our overall introduction to the program itself, Junior Environmental Explorations, is required for all new juniors. The lesson plan was written by former Associate Head of Nature Programs, Russ Brummer, as part of his Masters Degree program at Antioch-New England. Russ is now head of the Science Department at the New Hampton School. The objectives are to get the kids comfortable outdoors, to get them observing, and to get them thinking about how what’s going on “out there” is related to them. Each day of the 5-day week, the campers explore a different aspect of the natural world. One day is devoted to the forest, another to our streams, others to our lake and swamp, to insects, and to rocks and minerals. The activities are outdoors, in the forest, in the stream or lake, and experiential. We look, explore, feel, smell, and listen. For example, in the forest, we ask the boys to lie down on their backs and look at the trees and sky above them. How many colors can they see? What sounds to they hear? What does it feel like when they dig their fingers into the soil?

Our overall introduction to the program itself, Junior Environmental Explorations, is required for all new juniors. The lesson plan was written by former Associate Head of Nature Programs, Russ Brummer, as part of his Masters Degree program at Antioch-New England. Russ is now head of the Science Department at the New Hampton School. The objectives are to get the kids comfortable outdoors, to get them observing, and to get them thinking about how what’s going on “out there” is related to them. Each day of the 5-day week, the campers explore a different aspect of the natural world. One day is devoted to the forest, another to our streams, others to our lake and swamp, to insects, and to rocks and minerals. The activities are outdoors, in the forest, in the stream or lake, and experiential. We look, explore, feel, smell, and listen. For example, in the forest, we ask the boys to lie down on their backs and look at the trees and sky above them. How many colors can they see? What sounds to they hear? What does it feel like when they dig their fingers into the soil?

We hope that by the end of the week, they’ll be interested enough to come back for more, and most do. Frequently, in their free time, they’ll head back, on their own, to some of the places they visited during the occupation, and explore further. If this happens, then we’ve succeeded in accomplishing our objectives.

Beginning Butterflies and Moths

We start out in the Nature Lodge asking the question, “What is an insect?” To answer this we use models and our extensive reference collection of insects from our area. Campers find out that insects have six legs, three body parts (the head, the thorax, and the abdomen), two antennae, and compound eyes (ones with many lenses instead of the single one that humans have). To demonstrate these, we have special glasses that a boy can wear to help him experience what it is like to look through compound eyes. We even have a little song that helps campers remember all of this. I wish I could sing it to you, but you’ll have to be satisfied with just the lyrics for now. Ask your son to sing it when he gets home.

Head, thorax, abdomen

Six legs!

Head, thorax, abdomen

Six legs!

Compound eyes and two antennae

Head, thorax, abdomen

Six legs!

Once we know what insects are in general, we can explore several different kinds—beetles, bugs, flies, dragonflies and so on. This finally gets us to the Lepidoptera (scaly wing in Latin), that is, butterflies, moths, and skippers. With a hand lens, campers can look at the scales and see the difference between butterflies and moths. All of this takes two days. In the meantime, they are encouraged to come in during free time to begin construction of an insect net. These are still made the same way as they were 75 years ago, with some mosquito netting sewn together for the bag, the bag sewn to a wire coat hanger bent into a loop, and the whole contraption attached to a stick made from a cut tree branch. Not particularly elegant, but quite utilitarian. Towards the end of the week we go out to our traps and local fields to collect. This gives us the opportunity to discuss the difference between collecting and accumulating, the reasons (scientific) for collecting, collecting ethics (one specimen only of each type), and methods for preserving and labelling collections.

Once we know what insects are in general, we can explore several different kinds—beetles, bugs, flies, dragonflies and so on. This finally gets us to the Lepidoptera (scaly wing in Latin), that is, butterflies, moths, and skippers. With a hand lens, campers can look at the scales and see the difference between butterflies and moths. All of this takes two days. In the meantime, they are encouraged to come in during free time to begin construction of an insect net. These are still made the same way as they were 75 years ago, with some mosquito netting sewn together for the bag, the bag sewn to a wire coat hanger bent into a loop, and the whole contraption attached to a stick made from a cut tree branch. Not particularly elegant, but quite utilitarian. Towards the end of the week we go out to our traps and local fields to collect. This gives us the opportunity to discuss the difference between collecting and accumulating, the reasons (scientific) for collecting, collecting ethics (one specimen only of each type), and methods for preserving and labelling collections.

As with all our beginning occupations, once a camper has taken the introductory occupation, he is ready to move on to more advanced topics. He might choose, for example, to continue learning about butterflies and moths or perhaps he’ll choose to explore in-depth a different category of insects, such as beetles, dragonflies, and ants. Most beginning occupations are open to all campers, from Junior 1 to the Lake Tent and most have a wide range of ages enrolled.

Advanced Occupations

Our advanced activities are designed to take campers to the next level. Most do not have set lesson plans but rather are more freeform, and hence can be taken repeatedly. For example, an advanced butterfly and moth class will involve considerable observation and collecting. We might explore (in the field, of course) such topics as camouflage, insect defenses, flight characteristics, mating behavior, feeding behavior, predators, and more. Of course, as summer progresses, the species that are in our surroundings will change so, even if a boy takes the advanced class every week, the class will still be different.

Our advanced activities are designed to take campers to the next level. Most do not have set lesson plans but rather are more freeform, and hence can be taken repeatedly. For example, an advanced butterfly and moth class will involve considerable observation and collecting. We might explore (in the field, of course) such topics as camouflage, insect defenses, flight characteristics, mating behavior, feeding behavior, predators, and more. Of course, as summer progresses, the species that are in our surroundings will change so, even if a boy takes the advanced class every week, the class will still be different.

Wetland Ecology

Wetland Ecology follows the beginning occupation, Ponds and Streams. We are fortunate to have excellent wetlands right on our campus. Our “Lower Lake” (to the left of the bridge as you enter camp) is actually a separate body of water from our main lake. It is a glacial kettle formed as the ice retreated. A block of ice was probably left behind, buried, and when it melted it created the lake. It provides a perfect setting for our Wetland Ecology occupation. Here we can see a textbook example of pond succession. Over time, floating plants trap sediments. These, in turn, provide a substrate for marsh plants such as sedges and rushes. These trap even more sediment which allows woody plants such as sweet gale, meadowsweet, and alder to grow. Finally, the decaying mass is sufficiently elevated that swamp plants, such as red maple can take root. It takes several thousand years to convert the open waters of a shallow kettle lake into a wooded swamp with a stream flowing through it. But since the conversion works from the outside in, at any point in time along the way, we can see the processes unfolding.

Of course, that is just the big picture. Each habitat, open water, marsh, bog, swamp, has its own set of plants, fish, insects, birds, and mammals. They are all there for us to observe. Some are quite exotic such as the insect-eating sundews that inhabit the bog areas, or the orchids that are sometimes found in the transition between bog and swamp. Throughout the occupation week we can explore and make the connections between the elements of the food webs and see what changes over time.

Specialized Occupations

Specialized occupations are those at the highest content level. For example, last week we had a class that focused only on Lichens. We’ve also had classes this year on ferns and decomposers, which match the special interests of some of our nature staff members. In years past, we had specialized occupations focusing on ants, caddisflies, dragonflies, and bees and wasps. This year, in week 3 (to be offered again in week 6) we taught Geo Lab, which consists of a series of field trips to sites of particular geologic interest-trips that usually last the whole afternoon. We did gold panning in the Baker River, explored the caves and glacial features of the Lost River Reservation, travelled to the Basin and Boise Rock in Franconia Notch, made a special geologic trip to the Palermo Mine, and visited the Sculptured Rocks area. These specialized activities may be offered only once or twice a summer, and each with 4 or 5 participants. They provide new challenges for our most interested campers so that even someone in his 8th summer can still find new and engaging areas of the natural world to investigate with us. Some boys have followed their passions into careers in the natural sciences. All seem to develop an interest in something that can give them pleasure throughout their lives.

Hybrid Occupations

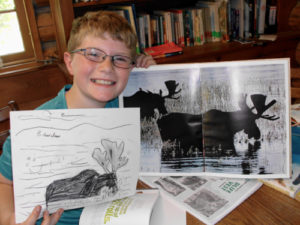

This category includes activities that combine nature and art, such as photography, nature arts and crafts, and environmental sculpture, and activities that combine nature with outdoor pursuits, such as bush lore, wild foods, and orienteering. With photography, we are following in the tradition of a long line of famous artists such as Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter and, in some sense, this is literal since we do black and white film photography (we have our own small darkroom) along with more modern digital photography. We try to go beyond snapshots so the campers learn to consider composition, light, shutter speed, focus and exposure when creating their photographs. The best negatives are printed in our darkroom and the best digital photos are printed out for display. Many will appear in our art show at the end of the summer.

This category includes activities that combine nature and art, such as photography, nature arts and crafts, and environmental sculpture, and activities that combine nature with outdoor pursuits, such as bush lore, wild foods, and orienteering. With photography, we are following in the tradition of a long line of famous artists such as Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter and, in some sense, this is literal since we do black and white film photography (we have our own small darkroom) along with more modern digital photography. We try to go beyond snapshots so the campers learn to consider composition, light, shutter speed, focus and exposure when creating their photographs. The best negatives are printed in our darkroom and the best digital photos are printed out for display. Many will appear in our art show at the end of the summer.

The combination of nature and outdoor pursuits has its roots in the skills needed for survival in ancient societies. The first class in each week’s Wild Foods occupation focuses on what it might have been like to live here 600 years ago. We imagine that we are part of the band of 20 or 25 Native Americans that might have been living here then. What food resources would we have had available to us? How could we store our food so that it (and our band) could last through the long New England winter? Who knew what plants were edible, and which were poisonous, and where and when were they available? How did they pass this information along? We continue to consider these questions as we enjoy whatever nature offers us that week. Last week, for example, we collected blueberries and had blueberry/cornmeal pancakes with maple syrup (made in Warner, NH by Pemi alum Bob Zock). We also made fritters with milkweed flowers and ate boiled young milkweed pods (and you thought milkweed was poisonous, right? It just has to be cooked properly to remove the toxins. Who found this out, anyway?) This week we’ve gathered some ripe chokecherries. These too are almost inedible when raw but delicious when cooked. They can be dried, like raisins, or made into a jelly, or even (just found this recipe) made into a soft-drink syrup that can be mixed with soda water to make a cooling summer drink. Speaking of drinks, we’ve made mint tea, birch tea, wintergreen tea, and rose hip tea, this from rose hips gathered here at camp last fall and dried. Later this summer we’ll make sumac tea, which tastes just like lemonade. Interestingly enough, all of this has had some practical applications for some of our campers. Boys on last week’s Allagash trip—of whom many were past Wild Foods occupation participants—reported that they found a large patch of mint and made themselves a big batch of refreshing mint tea.

Conclusion

I hope that this brief summary has given you a peek into our varied instructional program. To find out more, why not ask your boys when they return home? Better yet, head on out into the woods, the lakes, the streams, and let them show you. Here at Pemi Nature, we always think that showing is better than telling.