- Education at Pemi

- Nature

- News

- Newsletters 2013

- Staff Stories

- Summer 2013

Newsletter # 7: Pemi’s Nature Program

Most people who are new to Pemi are struck by the breadth of opportunities offered. Indeed, we encourage our campers to stretch their boundaries of experience by exploring our four program areas: Sports, Nature, Music Art & Drama, and Trips. However, we like to think that equally impressive is the depth of instruction that an older camper can enjoy should he choose to hone his skills in a particular area. This past Sunday, several of our 15-year old campers spoke on the role that Pemi has played in their lives. Matt Kanovsky, in his 8th and final year as a camper, reflected on his experience with Pemi’s Nature Program and how he was able to dig deeper and deeper as his interest in the natural world grew. How fitting, then, to have Larry Davis, Director of Nature Programs and Teaching, offer this week’s newsletter, in which he describes how this particular program area has responded to the “thirst for more” from campers who develop passion and focus.

Pemi’s Nature Program encompasses a wide range of activities including collecting trips, day-long excursions to places such as Crawford Notch, informal outings, and overnight caving trips. But the heart of the program is our formal instruction, which takes place during the occupation periods. Each week we offer 14-16 different activities over a range of “skill” levels, from beginning to advanced. For example, during Week 6 we taught at the beginning level: Rocks and Minerals, Butterflies and Moths, Ponds and Streams, Junior Nature Book, Birding, and Nature Drawing; at the intermediate level: Wild Foods, Digital Photography, Rocks and Minerals, Darkroom Photography; and at the advanced level: Mosses, Caddisflies, Butterfly and Moth Field Studies, Reptiles and Amphibians, and Bush Lore, for a total of 15 choices. Over the course of the summer, we offered a total of 37 different activities. Some appear every week, others appeared a couple of times, and a few appeared only once.

In this newsletter, I want to tell you a bit more about our occupations. While I will describe a range of these, I want to focus especially on some new, advanced ones that we developed this year. Our hope was not only to offer some challenges to the campers who spend a lot of time with us in the Nature Lodge, but also to give everyone a chance to explore aspects of our environment that they might not have noticed in the past.

Traditional Occupations

Some of our boys come to us with extensive experience in nature field studies. However, most do not. So, we want to offer attractive activities, in a variety of areas, that will allow them to begin their exploration of nature. While time and space do not allow a detailed description of these, I can discuss some of the characteristics that these “introductions” share.

First, our overarching objective is to get the boys to look at and observe the world around them. We want to help them “see.” This idea is stated in our Mission Statement for the Nature Program (modeled after one written by Allen H. Morgan of the Massachusetts Audubon Society):

First, our overarching objective is to get the boys to look at and observe the world around them. We want to help them “see.” This idea is stated in our Mission Statement for the Nature Program (modeled after one written by Allen H. Morgan of the Massachusetts Audubon Society):

To capture the attention of the inquisitive mind, bring to it an affection for this planet and all of life, and to foster an intelligent understanding of man’s position in the natural balance of things.

In order to do this, we have to take them out into nature, not just talk about it. We want to show them, not just tell them. Our 600 acres provide us with a wonderful variety of plants, animals, rocks, and more to look at, and we can easily access most of what we need to see during an occupation week of five, 50-minute periods.

Second, all our beginning occupations have set, detailed lesson plans. Our objectives include introducing the boys to the “nature” of the subject matter. For example what “makes” an insect or a butterfly or a moth. Or, “what’s” a mineral? We also want them to learn how an animal lives, how a mineral is formed, why some plants like shade and others like full sunlight…. We want them to learn about basic collection and preservation techniques. Finally, we want them to become familiar with some of the basic terminology that scientists use to describe things, not too much jargon, but enough so that they can read further if they wish (and many do).

Second, all our beginning occupations have set, detailed lesson plans. Our objectives include introducing the boys to the “nature” of the subject matter. For example what “makes” an insect or a butterfly or a moth. Or, “what’s” a mineral? We also want them to learn how an animal lives, how a mineral is formed, why some plants like shade and others like full sunlight…. We want them to learn about basic collection and preservation techniques. Finally, we want them to become familiar with some of the basic terminology that scientists use to describe things, not too much jargon, but enough so that they can read further if they wish (and many do).

Lastly, we hope to bring them to the point where they will formulate their own questions. “Why do moths fly toward light?” “Why are the leaves on the seedlings in the forest so big?” “Why can’t the piece of coal that I found in Mahoosuc Notch come from there?” Science is about questions, not memorization of facts. You must seek answers directly from nature and only observation of what’s “out there” can lead you to them. This gets us back to the first objective that I mentioned, getting the boys to look at and observe the world around them. If they do this then the questions (and maybe, the answers) should follow.

Staff

If we are successful in our introductory occupations, then we leave the campers wanting more. In order to provide this, we need staff with specialized knowledge. Beyond that, they also need to understand about teaching in the outdoors and that is one of the reasons why we run a pre-season Nature Instruction Clinic.

This summer we worked hard to find staff that could fill some of the gaps in our knowledge base. As most of you know, both Deb Kure (Associate Head of Nature Programs) and I are geologists. While we have extensive knowledge of most things natural, it is generally of the self-taught variety. We have always had a “bug person” too, most recently, Conner Scace (who was back with us as a visiting professional this year). His bug “specialties” are ants, wasps, and bees, along with dragonflies and damselflies. We wanted staff with formal training in ecology, wetlands, other insect groups, and related areas such as nature photography. We were very fortunate to find excellent people to fill our gaps. I’d like to reintroduce them to you.

Daniel (“Danno”) Walder has a degree in conservation biology from Plymouth University in England. He has done research on bracken in the British Isles and has also worked on projects in Mexico and Spain. Prior to arriving at Pemi, he spent many weeks trekking in Sri Lanka. He comes from a farming family. His knowledge of ecology and wildlife is extensive.

Kevin Heynig is studying for a degree in biology at Northern Michigan University, with an ecology concentration. His interests focus on aquatic insects and their environments. He has done research on caddisflies in Lake Superior and field research on other aquatic insects.

Mark Welsh is studying biomedical science at the University of Dundee. Besides his abilities in biology, he is also a serious photographer who works with both film and digital media. He said in his application materials, “Photography is a great passion in my life and I would relish any opportunity to pass it on to anyone, be they young or old!”

Matt Cloutier will be entering Middlebury College this year, studying for a degree in biology with an emphasis on entomology. Matt became passionate about butterflies and moths as a Pemi camper and, in 2011, was the 12th recipient (since 1974) of the Clarence Dike Memorial Nature Award.

Conner Scace (Visiting Professional) just completed his M.S. degree in environmental science at the University of New Haven. He did thesis work, with me, on fish populations in interior ponds on San Salvador Island, Bahamas. In the fall he will be entering a one-year-long program that will end with his becoming a certified biology teacher in Connecticut. As I said above, his passion is ants and related insects. We were very fortunate that he was able to join us for three weeks this summer.

Stephen Broker (Visiting Professional) is newly retired from teaching ecology in New Haven Public Schools. He also taught wetlands ecology at the University of New Haven. He is the Connecticut State Bird Recorder and an expert in “reading the landscape,” that is, reading the record of human occupation from characteristics of the landscape as seen in the field. Steve’s father was waterfront director at Pemi in the late 1930s so his week with us was, in a way, a homecoming for him.

New Occupations

While we have always had “advanced” level occupations in butterflies and moths, geology, and various insects, and specialty occupations in non-flowering plants, wild foods, photography, and wilderness skills, the backgrounds of our staff allowed us to offer many new and even more advanced activities this summer and to substantially update some that we have offered occasionally in the past. It is worth listing them all below before I use the rest of my time and space to describe a few of them.

Caddisflies

Bees and Wasps

Ants

Aquatic Insects

Dragonflies and Damselflies

Butterfly and Moth Field Studies

Ecology

Animal Homes and Signs

Reptiles and Amphibians

Wetlands Ecology

Bush Lore

Reading the Landscape

Mosses

Advanced Darkroom Photography

Mushrooms

Caddisflies

Caddisflies are aquatic insects with a two-stage life cycle. The larvae are fully aquatic and most build cases out of twigs, stones, or leaves. They feed on detritus, small insects, and plants. The cases serve as both camouflage and protection. But, since they have to drag them around while foraging, the construction material depends on how heavy they need to be to keep the larva from being washed away. So, if the habitat is a stream, then sand or small pebbles are used. If a shoreline or quiet pool, then leaves or twigs might be the choice. In fast-moving streams, the cases are attached directly to rocks and, rather than foraging, the larvae wait for the stream to bring food to them. The case construction and design is specific to a specific species (which in turn is adapted to live in a specific habitat). The adults are the reproductive stage and, as is common with many aquatic insects, they do not feed. All of this forms the background for this specialized occupation. Both adults (they fly readily to light) and larvae (along with their cases) can be collected and observed. Most important, however, is the observation of how they adapt to their preferred habitat and the questions about why they have those specific adaptations. This can lead to thinking about trade-offs between protection and energy expenditure for foraging versus the energy obtained from the food. We have at least 30 different kinds of caddisflies here (maybe more as we are just beginning to look at them) so the possibilities for study are wide.

Ants

Of course, anyone who’s ever had a picnic, knows about ants. They are everywhere. At Pemi, we have at least 10 kinds and some, such as carpenter ants (they tunnel and bore into wood) and Appalachian Mound Builders (they bite) are troublesome. Regardless they all display a sophisticated level of social organization that can be observed both in the field and in captivity. Our ant occupation includes study and discussion of social organization, observation of foraging behavior, collection of examples, collection of queens, and temporary establishment of captive colonies for observation in the Nature Lodge (later released back into the environment). Sometimes we get to observe ant “wars” where two separate colonies battle over territory. The questions that can be generated are legion. How and why did ants develop the social structures that they have? What are the advantages of this structure? Why are almost all ants female and almost all sterile (except the queens)? As always, we try to generate answers to these by observation in the field (which includes the uncertainties) rather than by looking up the answers on the internet (which, of course, are always right).

Ecology

Ecology is, of course, a very broad field of study. The main purpose of this occupation is to teach the campers about data collection techniques, analysis, and interpretation. This summer, we looked at plant distribution and diversity in several Pemi habitats including grassy fields, open meadows, and the forest floor. The basic tools for this work include a “quadrat” (basically a one-meter-square “frame” that can be placed anywhere), a hand lens, and identification books. The quadrat is used to “select” areas of equal size and all plants and animals within it are counted and catalogued. Our grassy fields are, of course, manmade habitats. Forest floors are in deep shade while open meadows are usually in full sunlight. This selection of habitats provides starkly contrasting examples of diversity (the number of different species) and population (the number of individuals of each species). What we found was that the manmade habitat was the least diverse (we prefer to have our grassy areas just grass and spend hundreds of millions of dollars assuring this result). The open meadows were the most diverse, with the forest floor in between (although with generally low diversity). These are, however, just facts and the fun comes from asking “why?” and then testing the possible answers to see what fits best. This is, of course, the scientific method. But, instead of just talking about it, in our ecology occupation we are actually doing it. Beyond that, this is no canned laboratory experiment. We are generating questions to which we really don’t know the answers.

Butterfly and Moth Field Studies

We have been collecting butterflies and moths at Pemi since the beginning of the Nature Program in 1929. Of course, back then, this is how nature was “done.” While we continue to collect butterflies and moths, we have tried to modernize it. We limit collection to just one of each species. We teach proper collection and preservation techniques. We strongly encourage the labeling of collections not only with the name of the species, but also with information about when and where it was collected. Still, this is only one of the ways that these insects are studied today. One important newer technique is to capture, mark, and recapture. This is a way of estimating population numbers. It works particularly well with butterflies. A location is chosen and butterflies are captured. But, rather than killing them, their wings are marked (using an indelible pen) so that the individual can be identified. Then, they are released. The key is to return to the same site on successive days. Of course, some of the captured butterflies will be ones that are already marked. In fact, the more days you do this, the more greater the percentage should be of marked butterfly recaptures. Through a series of arithmetical manipulations of the data, it is possible to estimate population numbers based on the proportions of new captures to recaptures. The real power of this technique is when it is used in successive years to observe population changes (and we intend to do this). The questions generated from the data (again, just “facts”) might include why different species have different relative populations, how populations change over time, how populations change with changing plant succession (could be coupled with the techniques of ecological quadrat studies), and much, much more.

We have been collecting butterflies and moths at Pemi since the beginning of the Nature Program in 1929. Of course, back then, this is how nature was “done.” While we continue to collect butterflies and moths, we have tried to modernize it. We limit collection to just one of each species. We teach proper collection and preservation techniques. We strongly encourage the labeling of collections not only with the name of the species, but also with information about when and where it was collected. Still, this is only one of the ways that these insects are studied today. One important newer technique is to capture, mark, and recapture. This is a way of estimating population numbers. It works particularly well with butterflies. A location is chosen and butterflies are captured. But, rather than killing them, their wings are marked (using an indelible pen) so that the individual can be identified. Then, they are released. The key is to return to the same site on successive days. Of course, some of the captured butterflies will be ones that are already marked. In fact, the more days you do this, the more greater the percentage should be of marked butterfly recaptures. Through a series of arithmetical manipulations of the data, it is possible to estimate population numbers based on the proportions of new captures to recaptures. The real power of this technique is when it is used in successive years to observe population changes (and we intend to do this). The questions generated from the data (again, just “facts”) might include why different species have different relative populations, how populations change over time, how populations change with changing plant succession (could be coupled with the techniques of ecological quadrat studies), and much, much more.

Bush Lore

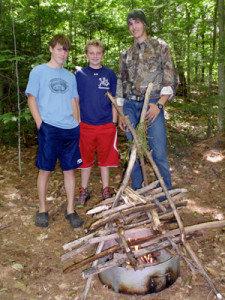

Besides natural history studies, our program also includes some introduction to wilderness and outdoor skills. Bush Lore was first introduced by Nuwi Somp in the 1990s. Nuwi brought the bush savvy that he gained in the jungles of Papua New Guinea to us here in New Hampshire. He built, with the campers, fish traps, snares, fish spears, and other tools using age-old techniques and patterns from his homeland. His only rule was that you had to eat whatever you caught. It turned out, however, that what worked in PNG did not necessarily work with our animals here—a very interesting lesson. This year we instituted a new version of this. It included map and compass reading, tracking, a discussion and simulation of hunting skills that would have been used by Native Americans here in northern New England, a discussion and simulation of field dressing of animals, shelter building, tinder bundle firestarting, and more. In other words, we tried to present, in five days, as complete a snapshot of ways to survive in the woods while living off the land as we could. This could also be followed by more advanced activities where we actually try to build skills in some of the shelter building, wayfinding, and tracking techniques.

Besides natural history studies, our program also includes some introduction to wilderness and outdoor skills. Bush Lore was first introduced by Nuwi Somp in the 1990s. Nuwi brought the bush savvy that he gained in the jungles of Papua New Guinea to us here in New Hampshire. He built, with the campers, fish traps, snares, fish spears, and other tools using age-old techniques and patterns from his homeland. His only rule was that you had to eat whatever you caught. It turned out, however, that what worked in PNG did not necessarily work with our animals here—a very interesting lesson. This year we instituted a new version of this. It included map and compass reading, tracking, a discussion and simulation of hunting skills that would have been used by Native Americans here in northern New England, a discussion and simulation of field dressing of animals, shelter building, tinder bundle firestarting, and more. In other words, we tried to present, in five days, as complete a snapshot of ways to survive in the woods while living off the land as we could. This could also be followed by more advanced activities where we actually try to build skills in some of the shelter building, wayfinding, and tracking techniques.

Conclusions

I hope that you have enjoyed this foray into our new, expanded list of occupations. We instituted these because we wanted to offer our campers a chance to go beyond introductions. Older campers need new challenges as they continue to return. We need to be able to keep the interest of both the boy who wants to specialize and the one who has been here for seven or even eight years and who wants something new. I believe that we have succeeded. We will continue to refine the occupations that we have instituted this summer (along with those that have been in place for years and years) and, I hope, produce new offerings in years to come.

~ Larry Davis

Director of Nature Programs and Teaching