- Education at Pemi

- Nature

- Newsletters 2021

Nature Studies at Pemi

Camp Pemigewassett Newsletter #3 (2021)

1970-2019: Fifty Years of Nature at Pemi

by Larry Davis

At the end of 2019, after fifty years of leading the Nature Program at Pemi, I stepped back and turned leadership over to Deb Kure. I have been asked to look back at the program I inherited, to discuss its evolution, and to highlight some of the changes that took place during my tenure.

The Nature Lodge

The Paul Moore Strayer Memorial Nature Lodge (as it is formally known) was built in 1929. Clarence Dike had begun his 42-year tenure as head of Nature Programs in 1927 and oversaw the building’s construction. By 1970, it was well established and well used. There was a single large room, open to the roof peak, with windows all around, two central entry doors, and a covered front porch. Inside, there were work benches along the walls on either side of the doors (four in all), a storage closet, two large display tables in the middle, and a large cage, big enough to house small mammals such as a chipmunk or squirrel. At the roof line, birch bark strips covered the inside walls. Attached twigs spelled out the names of the various nature activities: “BIRDS”, “ROCKS AND MINERALS”, “FLOWERING PLANTS”, and more. Two glass-fronted display cases held our reference collection of insects, and display mounts containing some arrow heads and spear points, a nine-leaved clover, severed bird wings, and other oddities covered the walls. Tanned animal skins—a silver fox and a woodchuck—were tacked to the front door. Natural light from the windows and two bare light bulbs provided all the inside illumination. It was very dark in the building in the afternoon and evening. Outside, there were built-in benches for sitting on the porch, some gardens containing flowers, a bank of ferns on the uphill side of the building, and a selection of trees, planted by Mr. Dike, in front of and at its ends, including two Balsam Firs and a Black Locust. These must have been put in early on as they were quite large by 1970.

In 2019 things had changed quite a bit, although the display tables, work benches, birch bark signage, glass-fronted display cases, and large cage (turned upside down to create a sloping worktable) were all still there along with the gardens, fern bank, and black locust tree. The biggest change was the addition of the Philip Reed Memorial Nature Library onto the west end of the Nature Lodge in 1993. This increased the available space by about 50%, and it now provides shelving for some of the 1000-volume library, additional teaching stations, storage space for camper collections, and display space for some of our spectacular rock and mineral specimens, along with artwork and more. In the main building, we’ve added much more lighting, one light (and one light switch) at a time, so now we are well-lit whatever the time of day. Until 2020, there were still skins on the doors, although different ones from the originals. In the late 1970’s, a third glass-fronted display case was added to house our beetle collection. A second storage closet came with the library addition. In the 2000’s, we put in a heavy, wide shelf along the east end of the building that could support our aquaria and a wild foods “kitchen” in the corner. A decade earlier, we had installed bookshelves along many of the window areas. These house our field guide and reference book collections. The library building houses books about nature, literary works, large format picture books, books about environmental and outdoor education, and some technical volumes. We also acquired a set of custom-built cabinets with drawers to house our growing rock and mineral collections. All of this supports our greatly expanded program (more about that later). Outside the building, the two balsam firs died (they only live about 75 years) and had to be cut down, while the gardens were expanded and replanted, mostly with native perennials.

Our Collections

We use collections at Pemi for display, reference, and teaching. In 1970, they consisted of the two glass-fronted cabinets containing pinned insect specimens mentioned above, and a few rocks on shelves. I established a policy of displaying only things that could be found in our area. My thinking was (and is) that “exotics” are nice but having them somehow implies that what we have right in our own back yard isn’t good enough. In addition, we hold our collections mostly for reference and teaching, not for a “wow!” factor. So, limiting them to local items makes sense. Augmentation began quickly during my first year. On staff at the time was Dr. W. David Winter, a pediatrician and serious amateur moth collector. Dave had been a Pemi camper in the 1930’s and acquired his interests under Clarence Dike. We set up light traps and took many collecting trips to nearby fields. Our insect collection quickly grew and improved as we added new specimens and replaced old ones that were tattered and worn. In 1971, we took our first afternoon trips to local mines and began to create a first-class rock and mineral collection. Our trips continue to this day, and in the 1980’s we commissioned a local craftsman to build us storage cabinets, accessible to campers, to house the collection. In 1977, John Ely was on staff. He was passionate about beetles and that year he and the campers added dozens of new specimens to the displays. There were so many, in fact, that he built the new glass-fronted display cabinet to house them. Throughout the years, we have continued to reorganize, add to, and improve our collections. Campers can see pinned reference specimens of most of the insects that they will see both in camp and on trips and can look at examples of the rocks and minerals in our area. Our instructors make good use of them, too, during activity periods.

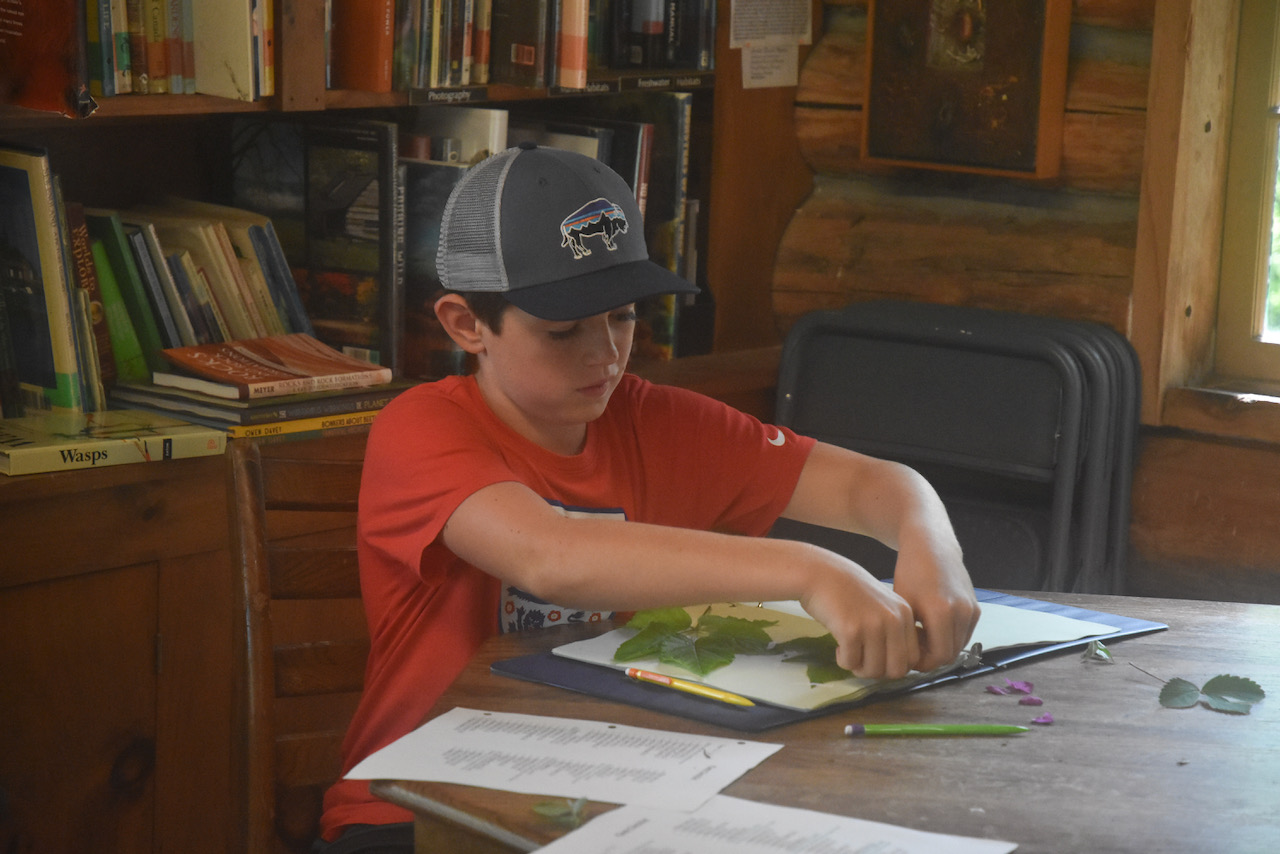

Instruction During Activity Periods

There have been huge changes in both the scope of our instruction and our approach to it. In 1970, activity periods (“occupations”) were two weeks long. Now they are one week. Campers chose three activities to do every day for the whole two-week period. Beyond that, they just signed up for “Nature,” and we’d have 20-25 in each of the three daily periods. There was no differentiation for age or experience and none for interests either. With generally only two instructors, we’d have to try to meet the needs of this eclectic group each day for the whole two weeks. It wasn’t easy and didn’t always lead to good outcomes (gauged by continuing interest, understanding, knowledge, and enthusiasm). In 1977, John Ely (the “beetle” guy mentioned above), asked if he could teach a nature occupation just about beetles. We went for it and it was a huge success. By 1978, we quickly converted our approach to specialty nature activities such as “Butterflies and Moths”, “Rocks and Minerals”, “Trees and Shrubs”, “Ponds and Streams” and so on. We mostly did collecting and classifying. But with camper questions and instructor interests, these activities became less focused on accumulation and grew to include more science, more exploration, more observation, and more “big picture” thinking. We started with just two instructors in 1970: Dave Winter and me. Dave was only at Pemi that one summer, but in 1971 we added two more, one of whom was future Director Rob Grabill, then just a rising Junior at Oberlin. Rob was passionate about sports and bugs. He brought his incredible charisma and enthusiasm to the program and participation grew accordingly. As the years progressed, we added more instructors, each with their own specialty, and each of them, in turn, added more activities to our program. Notable amongst these was Russ Brummer, a graduate student in Environmental Science at Antioch-New England. Russ did part of his master’s degree work at Pemi, creating a lesson plan called “Junior Environmental Explorations,” specifically designed to introduce Juniors (8-10 years old) to Pemi’s natural world with explorations of the forest, the pond, the streams, the rocks and more. It was a big success and became a required activity for all new Juniors. We still teach it today. In 2019, a comprehensive program covered all aspects of our natural environment at Pemi, and it included “fusion” topics such as Environmental Sculpture, Nature Photography, Nature Writing, Dying and Weaving, Wilderness Survival and more. Our instruction was science-based, hands-on, and inquiry-based. It was also place-based, meaning we focus on what we have right here, exploring our own property and then expanding out, first, to places nearby and then a bit further afield on half and whole day nature trips. Our philosophy has always been, “Show, don’t just tell,” which forces us to have examples right close to hand. Finally, I need to mention the Nature Instruction Clinic that Pemi runs in early June for staff from other camps, outdoor and environmental education, and interpretive centers. (The clinic can qualify for graduate or undergraduate credit through the University of New Haven). The program was begun in 1993 by Russ Brummer, Rob Grabill, and me, and a member of our first class was Deb Kure, Pemi’s current Head of Nature Programs. It led her and many other participants to careers in Environmental Education, something that we are immensely proud of.

Instruction Outside of Activity Periods

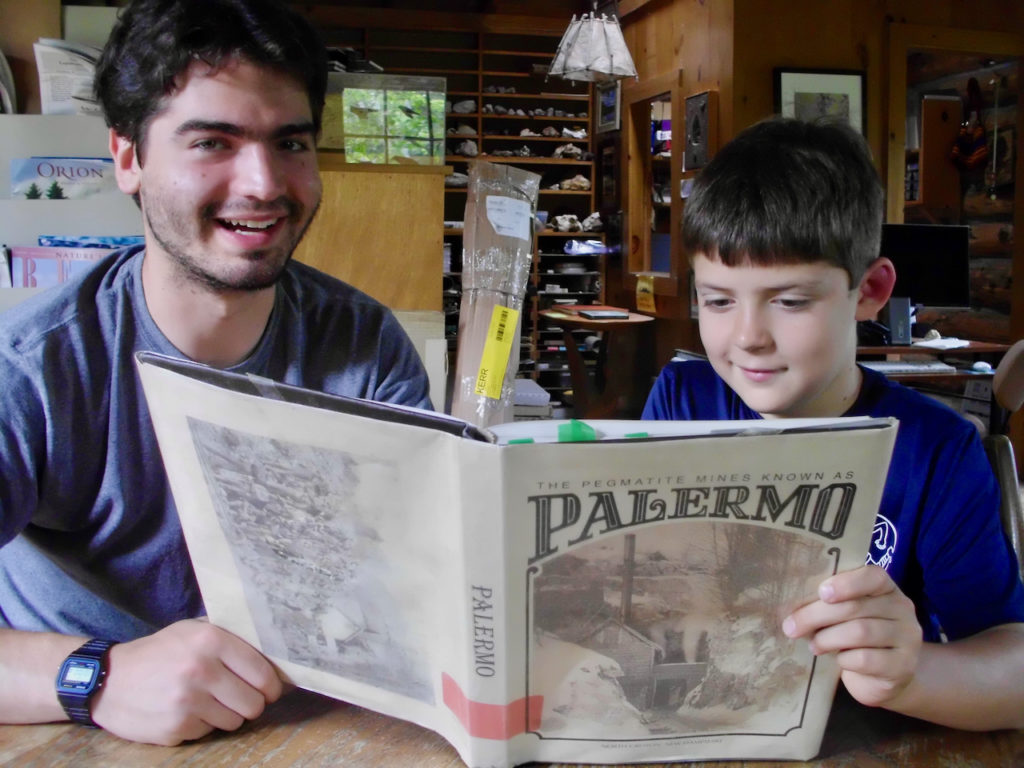

Not all instruction happens during Activity periods. In 1970, this type of “teaching” took place through labeled exhibits and the “What-is-it?” contest. Principal amongst the exhibits was the “Tree Walk.” This was (and is!) a self-guided walk that included 35 different trees. Each had a plaque that identified the tree, provided some interesting facts and “lore,” and gave directions to the next tree. Inside the Nature Lodge, temporary exhibits of plants, rocks and other items of interest occupied the two big display tables. The “What-is-it?” contest was a season-long competition involving nature knowledge. Each day, a new specimen was placed on the “What-is-it?” shelf. Campers and staff had to identify it and write the answer on a slip of paper, along with their name and cabin, earning points for correct, or nearly correct answers. At the end of the season, winners of the most points (one camper in each division and one staff member), received a nature award (more on awards below). I am happy to report that all of these instructional activities were still there in 2019. Nature staff updated and expanded the tree-walk a couple of times, most recently in 2020. Yes, that’s after my time “span,” but the changes were so extensive that it bears mentioning. New displays still appear periodically on those same two tables (repainted many times), and the “What-is-it?” contest continues to roll merrily along. Beyond this, we added an extensive nature trip program. We began taking rock and mineral collecting trips to local mines (Pemi is in the heart of an old mining district) in 1971. In 2019, we were still visiting some of these, most notably the Palermo Mine in North Groton, NH. This site, now worked only for mineral specimens, is world-famous. It has over 110 different minerals, with ten found nowhere else (including “Palermoite,” named for the mine). The owner has graciously allowed us access over the years; we even have a set of keys so we can go when we want to. We also instituted some longer day trips to sites of geologic interest such as Franconia and Crawford Notch, Sabbaday Falls, the Baker River for gold panning, and more. Many of these trips also include a Nature Photography element. Finally, as a cave scientist, I instituted caving trips to the Albany, New York area during the 1980’s. Over the years, we also have traveled to the Lake Champlain Islands for fossil collecting and to the Connecticut Lakes Region of NH to experience boreal forests and their unique flora and fauna.

Philosophy

Pemi’s philosophy of teaching about Nature has changed profoundly. In 1970, it was almost all about collecting. In fact, awards celebrated the largest collection (the greatest number of specimens) in each subject area. You might think of this as “competitive nature.” Mr. Dike would “seed” the streams with minerals from all over so that there would be a variety of things for budding rock-hounds to collect. Campers occasionally found some of these as recently as ten years ago. Any reader who has gotten to this point will have realized by now that there have been big changes in how, and why, we do things. One of the very first changes I made in 1970 was to shift to a science-based program and to consider different natural “objects” as part of a larger whole. I also defined the award criteria, with this guiding principle:

Nature awards are not necessarily presented for the largest collection in a given field or for participation in a given activity, but rather, they are awarded for the care in assembling and labeling a collection, knowledge of the areas of interest, the ability to recognize specimens in the field, overall interest and expertise, and the ability to work unselfishly with others.

We also created a mission statement for the program:

To capture the attention of the inquisitive mind, to bring to it an affection for this planet and all of life, and to foster an intelligent understanding of humans’ position in the natural balance of things.

—after Allen H. Morgan (former Executive Director, Mass. Audubon Society)

We want our campers to become observers of the natural world and to revel being out in it. We hope that understanding what they are seeing and how it all fits together will help them to become better citizens. We hope that their time in the Nature Program at Pemi will lead at least a few to careers in the natural sciences. We want them to gain a sense of place, wherever that place may be. We hope that they will share their joy with their friends and family, both now and in the future. Everything we do is aimed at achieving these goals.

Reflection and Moving Forward

I hope this has given you a feel for the changes in Nature at Pemi over the fifty years from 1970 to 2019. One of the wonderful things about Pemi as a whole is that we are always evolving. This is also true of the Nature Program. While I hope to continue teaching Nature at Pemi as long as I can (Clarence Dike made it to age 79!), Deb Kure assumed full leadership of the Nature Program in 2020. Eminently qualified for the position, she has begun to make it her own just as I did in 1970 and as Clarence Dike did in 1927. Her vision has already resulted in new approaches that have improved many aspects of what we do. I applaud them. That, however, is now Deb’s story to tell. I leave its telling (and the program) in her capable hands and anticipate watching, with pleasure, as Nature Studies at Pemi get even better.

–Larry Davis