- Camp Pemigewassett

- Education at Pemi

- Nature

- Newsletters 2014

Field Trips Near and Far: Pemi’s Nature Program

Summer 2014: Newsletter # 7

EXCURSIONS

by Larry Davis, Director of Pemi’s Nature Program

Pemi’s Nature Program has many facets. One of these is our program of instruction. This summer we offered forty different nature occupations ranging from classics—Beginning Butterflies and Moths and Beginning Rocks and Minerals (both available every week)—to more esoteric activities such as Mushrooms/Mosses/Lichens, and Bees/Wasps/Ants offered just once apiece. New this year was the “GeoLab” series of advanced geology occupations focusing on topics such as Plate Tectonics, Water and Geology, and New Hampshire Geology. Along the way we also made good use of our dark room, our microscopes, our wildlife camera, and our wild foods “kitchen” (ask your boys what was on the menu).

I want to use this opportunity, however, to highlight another aspect of the program: the afternoon (or longer) field trips that we take away from camp. Some of these are to nearby old mines for mineral collecting or to nearby fields for butterflies. Others are to more distant localities such as Franconia and Crawford Notches here in New Hampshire or to the cave region in Schoharie, New York.

This summer, in addition to the mine and butterfly trips, we enjoyed several of these longer excursions. Two went to the Notches (one each to Franconia and Crawford), one to Quincy Bog in nearby Rumney and one to New York State for caving. In addition, our new GeoLab occupation included field trips to Sculptured Rocks in Groton, NH, Plummer’s Ledge, here in Wentworth, Livermore Falls in Campton, NH, the bluffs and terraces along the Connecticut River in Fairlee, VT, and the Baker River, where we panned for gold, and one special excursion to the Palermo Mine (a regular stop for us) for our GeoLab campers that focused on local geology. I will use the rest of this newsletter to describe some of these trips for you, and have provided links that give the locations of most of the sites. With the exception of the Palermo Mine, they are all open to the public.

Quincy Bog (Rumney, NH)

Marshes, Bogs, Swamps- Bogs are wetland areas dominated by sphagnum moss. Swamps are wetland areas with trees growing in them. Marshes are flooded areas dominated by floating plants, grasses, and sedges. Quincy Bog is not just a bog. It is a beaver swamp and pond. Regardless of the name, this is a special place, not only because of what’s there, but also because of how it came to be preserved. This is what they say in the trail guide:

Quincy Bog is a special place. The forty-four-acre Natural Area includes the remains of a post-glacial lake (now reduced to a one-acre open bog pond). Its bog pond, sedge meadow, red maple and alder swamp, sandy flood plain, granite outcrop, and typical central New Hampshire cut-over woodland present a rich diversity of plant and animal life that we invite you to contemplate and explore.

Beavers, still very active today, formed the “bog” itself. Along the trail that circles the flooded area, you can see their dams, lodges, stumps (both new and old) of trees that they’ve cut down, and skid ways that they’ve used to move the trees to the pond where they can float them to the dams or lodges. You also experience the entire ecological community that exists because of the beaver’s transformation of a stream. Visitors see turtles sunning themselves on logs, a huge variety of birds, frogs, along with an abundance of plants—ferns, trees, mosses, flowers, sedges, grasses, and the fungi that “infect” them.

The trail itself changes elevation so that you move from a wetland community that includes red maples, sedges, ferns, and floating plants, to a hardwood forest with oak, beech, white pine, and wintergreen in only a few vertical feet. It is a good lesson in how small changes in elevation can lead to big changes in plant and animal communities. At one point there is an old stone wall and a very old oak tree—at least 150 years. In another, there is a rock outcrop covered with “rock tripe” (a lichen). There are large glacial eratics and a flowing spring. If you walk the trail clockwise (any we usually do), you come, at last, to the large beaver dams (old and new) that help to form the pond.

Equally interesting is how this “Natural Area” came to be protected. As you drive here, you pass through what looks like a typical suburban subdivision. Indeed, this was supposed to completely surround the bog, which, in turn, was going to be partially drained. A group of citizens became alarmed and moved to protect it. One of the leaders of the group was a man named George Wendell. George was a retired Plymouth fireman living in Rumney. He also was, for many years in the 1970’s and 80’s, Pemi’s “shop guy.” Today the bog is owned by a non-profit, “Rumney Ecological Systems,” that has a large board of directors composed mostly of Rumney residents. The community lovingly cares for the bog and there is even a nature center where nature programs are presented monthly. It is truly a place of pride for the citizens of Rumney.

Palermo Mine (North Groton, NH)

In a 1994 Pemi newsletter, I wrote the following about the Palermo Mine:

Huge piles of shining rock glistening in the hot afternoon sun. The light reflected off these rocks is almost blinding. The road fairly sparkles with flakes of mica. In every direction are more dumps, more piles of rock, more shafts—on the hills, in the impoundments in the woods. Scampering over the dumps are the figures of excited campers. They look dark against the white quartz and feldspar. Their arms too, sparkle with mica flakes. The sound of clanging rock hammers are accompanied by excited shrieks of “Larry-look what I found!” We have visited this mine over 75 times in my 25 years here. It was the first one that we went to (and it was also the site of our most recent trip). It never fails to delight and it still yields new treasures. Palermo has launched many a Pemi camper’s career in Geology.

This description is as accurate today as it was twenty-one years ago. It is, in fact, a world-famous mineral locality. There are about 120 minerals that occur here including about 10 that are found nowhere else in the world. It is an exciting place to visit. The owner, Bob Whitmore of Weare, NH is still working the mine for mineral specimens. In addition to the rare minerals, which are of interest to collectors, it yields beautiful, gem-quality aquamarines, commercial quantities of quartz (the concrete at Boston’s Prudential Center contains crushed white quartz from Palermo), mica, and beryl, nice apatite crystals, and many, many other easily found and identified minerals. It was originally opened in the 1870’s for mica, which was used in stove windows (still is, in fact) and automobile windshields. It was also a source of feldspar, which was used in the large refractory (pottery) industry that existed up and down the Connecticut River (there were rich clay deposits from Hartford, CT up to St. Johnsbury, VT).

We are very fortunate that Bob is a friend of Pemi. The public is not allowed in, but we have a key and can go any time we like. We generally visit every Thursday but we have also taken some additional trips. This year, as part of the GeoLab occupation, we went with 3 older campers to look at the geology in some detail and to collect from parts of the mine that we do not usually go to. Bob has also donated some spectacular mineral specimens to us. These are displayed in a case (that Bob built for us) in the Reed Memorial Nature Library.

Panning for Gold (Baker River, Wentworth, NH)

Yes, there is gold in New Hampshire! In the 1840’s there were actually active gold mines in Lyman and Lisbon, about 40 miles north of here near the Wild Ammonoosuc River. These never amounted to much, but you can still find “placer” gold (loose gold particles mixed in with the other sediments) in that river and in the Baker, which runs from the slopes of Mount Moosilauk through Warren and Wentworth to join the Pemigewassett River in Plymouth, NH. During a GeoLab excursion last week, Deb Kure and 3 campers tried their luck. They used old-fashioned gold pans leant to us by maintenance staff member Jeremy Rathbun who pans for gold as a hobby. He also suggested a good location for our first attempt ever: in the river just by the town ball field in “downtown” Wentworth. The idea of gold panning is the gold is very, very heavy compared to the rocks and minerals that comprise the river gravels. As the stream slows in spots, the heaviest sediments drop out first. So the search for gold begins in the river’s pools. You scoop up gravel, sand, and water with the pan and gently swirl it around. The lighter materials go to the outside and the heavier (gold?) stay in the middle. What you’re looking for is called “color” by those in the know. Our group did see some “color” and picked out tiny grains with equally tiny tweezers and put them into (you guessed it) tiny glass vials filled with water. Needless to say, nobody’s fortune was made, but it was so much fun that we’ll try it again next summer. I hope you’ve enjoyed these “nuggets” of information about New Hampshire gold (sorry-couldn’t resist a pun).

Plummer’s Ledge (Wentworth, NH) and Sculptured Rocks (North Groton, NH)

These are two, state-owned, “pocket” parks that are outstanding locations to view the work of glacial melt water. Sculptured Rocks still has water flowing through it (the Cockermouth River), while at Plummer’s Ledge the glacial features are high and dry deep in a New Hampshire woodland.

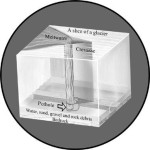

Today’s mountain streams, here in New England, are crystal clear. That is, they contain no suspended sediment (which would turn them cloudy or brown). Without these sediment “tools” almost no erosion of our hard bedrock could take place. Not so in glacial times. Not only was there orders of magnitude more runoff, but it was loaded with sediment from silt to boulder size. The swirling waters flung the sediments against the bedrock of channel floor and walls smoothing them and carving flutes, chutes, and deep potholes. At Sculptured Rocks, these are clearly visible along the modern course of the river over a few hundred-foot long span. At Plummer’s Ledge, the potholes are big and surrounded by woods.

While potholes dominate both of these sites, their formation was different. Sculptured Rocks was probably formed by glacial melt water out in front of the glacier. Had you been there at the time, you would have seen the rushing stream pouring out from the front of the ice, carrying huge amounts of sediment of various sizes from small (silt) to large (cobbles and boulders). These formed the potholes that are visible today. At Plummer’s Ledge, the melt water was on top of the glacier. It plunged down a crevasse (also known as a “moulin”) into a plunge pool in the bedrock below. Both sites are excellent reminders that the hills and mountains of New Hampshire were once covered by ice almost a mile thick a mere 15,000 years ago…a very, very short time when placed on a geologic time scale.

River Terraces, Flood Plains, and Faults (Connecticut River, Orford, NH/Fairlee, VT)

Many of you have probably crossed the bridge over the Connecticut River between Orford, NH and Fairlee, VT. It is a quirk of political geography that the state line is actually on the west (Vermont) side of the river, rather than down the middle. So, the whole width of the river is actually in New Hampshire.

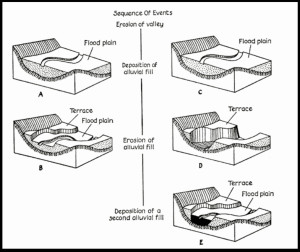

This is one of the best places that I know to view river terraces. These are also products of glaciation. In this case, their origin lies in Connecticut, at Rocky Hill, where a plug of glacial outwash dammed up the ancestral Connecticut River creating a lake in front of the retreating glacier. This lake, known as “Glacial Lake Hitchcock” eventually stretched as far north as St. Johnsbury, Vermont. As lake levels went up and down, the adjacent flood plains became stranded creating terraces. There are at least 4 distinct levels that can be seen on both sides of the river. In the early 1800’s, Orford was a center of commerce and a crossroads on several major trading routes. Retired sea captains built spectacular houses on one of these terraces. They are classics of the federalist style and were designed by Asher Benjamin, an architect in Charles Bullfinch’s firm in Boston. Bullfinch was the designer of the Massachusetts State House in Boston and the U.S. Capitol building in Washington.

Over most of its course, the Connecticut River actually follows a major fault. However, a body of unerodable granite forced the river to divert to the east around it. It now appears as a cliff (“Mount Moriah” or “Mount Morey” depending on which map you look at) on the Vermont side. It is an important nesting location for Peregrine Falcons, which can sometimes be seen from the parking lot of the Fairlee Diner (an excellent place for breakfast or lunch). As you can see from the map, Lake Morey is actually located along the fault. If you are driving south on I-91 from St. Johnsbury, looking south a couple miles north of Bradford (Exit 16), you can clearly see, straight ahead, Lake Morey and the valley that follows the fault while the road turns east to follow the river.

The fault is a major geologic divider. The rocks in New Hampshire (east of the fault) are mostly igneous (hence the nickname, “The Granite State”). To the west, in Vermont, they are mostly metamorphosed sedimentary rocks that were deposited on the floor of an ancient (~ 400 million years ago) sea. The cliffs at Fairlee are geologically part of New Hampshire despite the fact that they are politically part of Vermont.

Livermore Falls (Pemigewassett River, Campton and Plymouth, NH)

This dramatic set of rapids and falls along the Pemigewassett River has a complex geologic history and an interesting human one. It is the “type locality” (the place the rock was originally found and described) for the rock “Camptonite,” a kind of basalt that has been found worldwide.

Geologically, you have a weakly metamorphosed rock (once sea-floor sediment) that has been injected with magma (molten rock) of two types. One is iron-magnesium rich, which produced the camptonite, the other was silica rich, which produced a type of rock known as “Aplite.” Both of these rock types have formed narrow tabular (like a tabletop) bodies that are almost vertical. These are known as “dikes.” Since the dikes cut through the metamorphic rock, they must be younger (if you’re going to cut a cake, the cake has to be there first). The dikes, however, are not metamorphosed. So the mountain building events that altered the original rocks must have happened after they were deposited but before the dikes were injected. In one or two places you can see that the aplite dikes cut through the camptonite dikes so they must be younger still. This yields a sequence of events for the region: first the sediments are deposited. Then the mountain building forces metamorphosed them. Next the camptonite dikes were injected and finally, the aplite dikes formed. This is how geologists go about figuring out the “story” behind what we see and Livermore Falls is a great place to teach about it.

The river also illustrates how these ancient features influence modern landscapes. The camptonite is weaker, both chemically and physically, than the metamorphic rocks. Geologists would say that it “weathers” more easily. So, where the dikes are exposed in the river’s channel, it has cut “slots” into the surrounding rocks. These are clearly visible on both sides of the valley. The presence of these weaker dikes, which cut perpendicular to the river, is probably also responsible for the falls being here.

From a human standpoint, the falls lead to the development of a water-powered mill here. According to the Campton Historical Society, this was a paper-pulp mill. You can clearly see the remains of a diversion dam that funneled the river into the turbines within the factory (also clearly visible). The mill was built in 1889 and was in production until the 1950’s. In 1973 a flood (Hurricane Agnes) destroyed the dam. This is the same storm that produced the famous “Pemi Flood” which forced us to bring campers in on boats on opening day that year.

There is also a wonderful old iron bridge, built in 1886. It is of an unusual “pumpkinseed” design. It stands 103 feet above the river and is 263 feet long. It was closed in 1959.

~ Larry Davis